Two of the world’s most historic and heritage-rich spirits, Scotch single malt whisky and Cognac, have evolved in distinct – and wildly different – directions. Equally, both have experienced oscillating levels of status and popularity across a number of centuries, starting out as an accessible product, becoming ‘premium’, and back again, and back again, et cetera.

In recent times though – it seems to me, at least – these two prodigious spirits have somewhat settled into their roles. Cognac has established itself, for the most part, as a high-end luxury, transcending even that accolade in places and developing a certain inaccessibility; a dustiness, perhaps. The exclusive domain of old men and Christmas pud; reminiscent only of leather-bound books and rich mahogany.

Meanwhile, Scotch single malt whisky has grown and slumped and grown over the last hundred years or so to become, as of this moment, a commodity spanning the length and breadth of the economic spectrum – at once elixir of the everyman and refreshment of the super-rich.

Whiskies from Speyside distillery Macallan can retail at anything from around £40 to well in excess of £30,000, and have sold at auction for more than £1,000,000.

This has led to the development of some interesting, widespread and often-incorrect preconceptions about the two drinks and their relationship to each other. So let’s lay it all out: Cognac vs. Whisky.

Production

The primary difference is a foundational one: whisky is grains, Cognac is grapes. Then, grains get beered, and grapes get wined. Then, the regulations kick in – Cognac is even more tightly-controlled than Scotch single malt whisky is – but honestly, from there on out, it’s all, for the most part, pretty similar.

Single malt Scotch whisky and Cognac are both distilled in copper stills – pot and alembic stills, respectively – a minimum of two times. Alembic stills are very similar to pot stills, the primary difference being in size and shape. The resulting spirit – ‘new make’ and ‘eaux-de-vie’ respectively – is then aged in oak casks.

A pair of alembic stills at Cognac Frapin.

The type of casks used does differ considerably: Cognac must, by law, be aged in oak casks (most commonly Limousin or Tronçais) that have not previously held a different drink, for at least two years. This means that any and all flavour and nuance in the spirit comes from the wood itself and the aging spirit, without any other influence, and while a degree of experimental maturation may be beginning to take place in the Cognac world, purity and integrity is crucial to Cognac culture.

Scotch whisky however, which must be aged in ‘traditional oak casks,’ has a lot more freedom to play where cooperage is concerned. Everything from virgin oak to ex-bourbon to ex-sherry and ex-sauternes casks (and beyond) can be used to age the spirit and impart flavour.

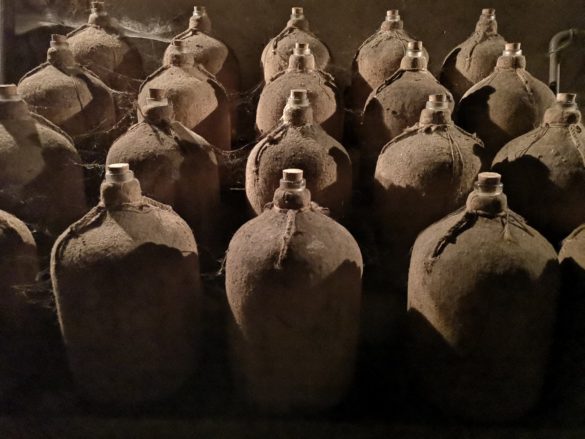

A final divergence in production between our spirited friends might be ‘paradis’ – a word used exclusively in relation to Cognac. Paradis refers to the final stage of aging that a Cognac or Cognacs might go through. Paradis cellars are home to the oldest barrels, into which (often) the oldest spirits will be decanted for their final maturation. Paradis barrels are so old as to have zero activity left in the wood itself, thus the aging becomes fairly neutral; purely oxidisation. From here, casks might be decanted into bonbonnes – large glass bottles – to be used in the house’s finest blends as and when required.

Bonbonnes in the paradis cellar at Cognac Frapin.

Taste

Brown spirits is brown spirits, amirite? NO, YOU’RE WRONG – but there are similarities. Whisky and Cognac’s differing origins make them fundamentally different drinks, but with enough cross-over to allow easy exploration and recognition.

Cognac’s fruity origins lend its spirit a gentler, juicier foundation across the board – an underlying grapiness sure to appeal to fans of fruitier whiskies. Meanwhile, the impact of French-oak maturation on eaux-de-vie is often to contribute a woody, spicy profile; characteristics equally familiar to whisky enthusiasts.

Meanwhile, whisky’s grainy roots create a fundamentally (in most cases) greener, more vegetal new-make. Maturation rounds off the spirit’s edges, and allows it to take on cask influence or simply for the distillery’s – and the spirit’s – inherent character to develop, both of which bring subtlety and nuance.

Malted barley, or simply ‘malt’ – where the flavour of Scotch single malt whisky begins.

Whisky also has a little more flexibility where its production methods are concerned. One of the biggest and most recognisable flavours in whisky is – love it or hate it – smoke. Smoky flavours in single malt Scotch whisky most-commonly come from the phenols found in peat smoke, which is used by some distilleries to dry out barley at the end of the malting process. Other whiskies might undergo a period of aging in a cask which previously held peated whisky, thus imparting some smoky flavour.

While some ‘smoky’ flavours can develop naturally in spirit – the influence of oak can sometimes develop in this way – and, indeed, many older Cognacs claim smoky notes in both their bouquet and palate, production restrictions mean that peat smoke is unlikely ever to be found in Cognac.

The seemingly-singular nature of Cognac’s barrels might, for some, cast a little doubt on the complexity and depth attainable in the French spirit. A single permitted cask-style, however, is far from the be-all-and-end-all.

Climate

Cognac houses utilise different cellar types to age their spirit in different ways, manipulating the humidity of their warehouses to achieve desired characteristics in the maturing spirit; wet cellars to create a softer, more subtle flavour profile, dry cellars to maximise the spirit’s interaction with the wood and create a vibrant, spicy character.

Dry cellars at Cognac Frapin.

There is an element of this climatic manipulation to be found in whisky, though perhaps a certain amount of it is simply incidental. Scotch whisky, for instance, can handle long periods of maturation: Scotland’s cool climate means that the angels’ share – the amount of spirit lost to evaporation – tends to sit at around 2-3% per year, and low temperatures mean that wood interaction tends to be consistent and at a reasonable rate, thus unlikely to overwhelm the inherent character of the spirit.

For some context beyond Scotch single malt, distilleries with warehouses in warmer climes have a whole different issue to contend with. Taiwanese distillery Kavalan matures whisky in a tropical climate, accelerating both wood interaction with the spirit, and the rate at which the whisky evaporates. The result tends to be relatively young whisky displaying a level of wood influence which it would take many more years to cultivate in a cooler climate (like that of Scotland), while the spirit itself has had much less time to age, oxidise and develop subtlety; in short, a very intensely flavoured spirit at, typically, quite a high ABV.

Blending

Cognac distilleries have never shied away from using product from other estates or using stocks from way back in their own storied histories to achieve a desired effect. And while whisky, too, can count on ancient stocks to beef up its blends, the pressure on whisky distilleries (Scottish ones in particular) to conform to age statements perhaps makes it much more unlikely to see older whisky mixed in with younger spirit.

How to drink them

Where whisky may have developed a certain puritanical culture, the modernisation of Cognac in recent years means that Cognac cocktails are in no short supply, and even simply mixing it is not out of the question.

French Connection: a simple mix of Cognac and amaretto.

The answer to this question in both cases however is simply, ‘however you like’. Though in the name of being helpful, we like to try everything neat and with water, at least to start with. This allows you to really explore the flavours of the spirit, without intrusion. The Perfect Measure Glass is perfect for this.

The Perfect Measure Glass is designed to deliver aromas and flavours to the mouth and nose in the just the right places, at just the right concentrations.

‘Why not a brandy balloon?’ We hear you cry! Well, simply put, there’s just too much space in there for volatile alcohol fumes to gather, masking rather than accentuating the more subtle flavours and aromas. For more on drinking Cognac, check out Billy’s entire blog post on exactly that.

Provenance and Terroir

Provenance – indeed, heritage – is as important (or as perceivedly important) in Cognac as it is in whisky. Indeed, provenance may be something some whisky distilleries choose to focus on, and which consumers may care about, but provenance in Cognac is enforced by law.

Whisky distilleries can ship in and use barley from anywhere they like. For instance, Indian distillery Amrut take pride in growing their own barley, but also in using peated and unpeated barley from Scotland to create particular flavours in their whisky.

Cognac houses on the other hand are required by to source their grapes from inside the Cognac region. Beyond even that, there are six sub-regions within the greater Cognac region or appellation*, but those are a deep-dive for another day. What we can establish is that these six sub-regions each impart different properties and flavours to wine and eaux-de-vie – a principle known as terroir – thanks to differences in the soil and climate of each region.

Ugni Blanc grapevines around Château Fontpinot in Cognac’s Grande Champagne region.

To use the name of a particular sub-region on their labels – each of which has differing levels of prestige associated with it – Cognac houses must source 100% of the grapes used to make a particular Cognac from that particular region.

Likewise, distilleries like Bruichladdich and Springbank both make a point of creating particular expressions to showcase local barley and thus the terroir whisky is able to display, but the very appeal of these releases and those like them could be said to lie in their uncommon nature.

The 2018 release of Springbank’s Local Barley series, crafted to showcase the impact that locally-grown ingredients can have on the spirit.

So there we go. Two brown spirits, aged in oak, decidedly different in character and flavour and yet, in the great venn diagram of delicious drinkable things, close enough that an easy exchange of sippable experiences is possible.

Fallen in love with Cognac? Cognac Show 2019 takes place in London this weekend(26-27 April) and you can buy tickets here.

Alternatively, check out our Top 10 Whiskies and Top 10 Cognacs, or continue your education with our Beginner’s Guide to Cognac.

*Grande Champagne, Petite Champagne, Borderies, Fins Bois, Bons Bois and Bois Ordinaires & Bois Communes.

Tagged cognac, cognac cocktails, cognac vs whisky, how to drink cognac, whisky

Enjoy responsibly

Enjoy responsibly

Recent Comments

Unfortunately, the answer is 'between 400g and 2000g per litre' :)

Posted on: 9 October 2024

What ratio of Sloe to gin is used, I see anything from 400 to 2000g of sloe to 1 litre of gin!

Posted on: 7 October 2024

What really makes Bob Harris' predicament in 'Lost In Translation' so absurdly funny is that he nailed it in one take, and the director just couldn't accept that.

Posted on: 11 January 2024