Vermouth. The blog that literally tens of you have been waiting for. As we learned last time, vermouth is a type of aromatised wine – which, to be honest, doesn’t sound very sexy.

The aromatised wine family – spot the vermouth

In fact, for most people, vermouth isn’t a very sexy thing. If cocktails were boy bands, vermouth wouldn’t be the charismatic singer or the dark, moody guitarist, it’d be the odd guy on the keyboard who gets significantly less fanmail than the rest of them. Yet, much like the spotty keyboard guy, vermouth’s presence is essential, and there is much to appreciate about it in its own right.

For our essential guide to vermouth, read on. But if you’ve been given a bottle and just want to see the best – and easiest – ways to drink it, jump to the cocktails section.

What is vermouth?

What we know as vermouth came into being in late-18th-century Turin, the culmination of centuries of people playing around with herbs and wine. It gained popularity thanks to the emerging café culture and the patronage of the royal family – as we know from Park Royal gin, regal taste is the best taste – and its manufacture was vastly aided by the proximity of Alpine botanicals and a large amount of vineyards.

Nowadays, there are strict rules about what vermouth is made of, how strong it is and what it’s called.

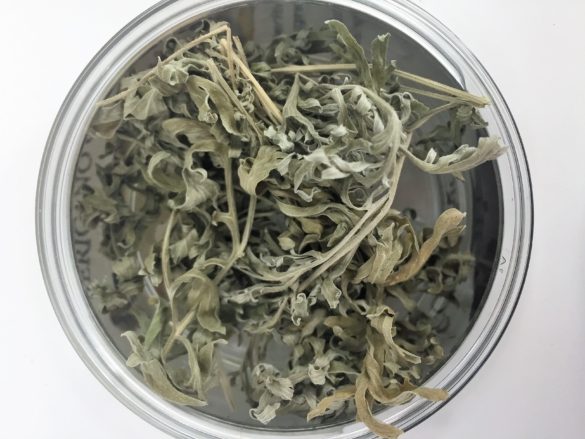

In terms of its composition, vermouth has to be at least 75% wine. This is then fortified – beefed up by the addition of more alcohol – and spices and herbs are added, most notably artemisia (wormwood), which must be included.

Artemisia Absinthium (wormwood)

The resulting vermouth must be between 14.5% and 22% ABV, and will fall into one of the following categories:

Extra Dry: <30g/l* of sugar (*grams per litre)

Dry: <50g/l of sugar

Semi-Dry: <90g/l of sugar

Semi-Dolce: <130g/l of sugar

Dolce: >130g/l of sugar

How is vermouth made?

Vermouth = wine + alcohol + sugar + herbs / spices. Simple, right?

Not exactly. Blending herbs, alcohol and wine in a way that doesn’t result in something disgusting is surprisingly difficult. I recently attended a masterclass run by the brains behind Cocchi vermouths, and their viticulturist Paulo Bava explained that they follows the recipes of Guilio Cocchi, who founded the company in 1891, because they are stable and produce reliably excellent results. Paulo constantly experiments to see if the recipes can be improved, but it is a painstaking process.

Problems start with the base material: the wine. Many producers will use a wine made specifically for the purpose, which is a nice way of saying that it’s not fit for drinking, but the best vermouths are normally those where the wine used can be happily imbibed on its own. Using these wines, however, also presents challenges: every vintage is different, with varying levels of tannin, colour, acid – which all interact with the herbs in different ways.

Those herbs are pretty pesky too. You can easily have more than 20 herbs in a recipe and getting the best from each requires a variety of different techniques, and choices – for example chamomile has a completely different flavour when macerated in alcohol than in water.

Then there’s the small matter of getting it to our glasses. Vermouth needs time to rest, sometimes many months, so that the flavours can properly integrate – vermouth tasted straight from the barrel can be undrinkable, even with the added sugar balancing the bitterness and aiding stability.

Making vermouth, therefore, is an art. But if you want the quick paint-by-numbers version:

Print it out and have a go at home

how to make vermouth

- Find spices and herbs.

- Macerate them individually in solutions of alcohol and water, using solutions, temperatures and times best suited to get the most out of the ingredient.

- Filter and press the solution to extract the flavour.

- Add the individual extracts to the wine, plus the sugar and the extra alcohol.

- Give your mixture time to relax in a barrel-shaped spa.

- Put it in bottles.

- Dazzle the world with your magnificence.

Should I be drinking Italian or French vermouth?

Vermouth is now made all over the world, but the two historic traditions for this aromatised wine come from Turin, Italy, and Chambéry, France. The latter adopted the fashion of vermouth from the former – both towns were in the kingdom of Savoy, after all – but developed a different style.

Whereas Turin most commonly used sweet Muscat wines as a base for vermouth, Chambéry used dry white wines – people therefore turned to the French vermouth for dry styles, and the Italian for sweeter ones.

Dolin Dry Vermouth

The Chambéry style has largely gone out of fashion, with Dolin being the last remaining producer, while Vermouth di Torino flourishes and now even has a protected designation of origin: if you buy something with ‘Vermouth di Torino’ on the label then it must have been produced and bottled in Piedmont using Italian wine, be between 16%-22% ABV, and Artemisia Absinthium must be one of the main ingredients.

There is also a premium version within this designation: Vermouth Superiore, which must have at least 50% wine from Piedmont and ideally only use local botanicals.

The answer to the question above is, of course, that you should be drinking the vermouth that most appeals to you. Decide whether you want to try the bitter red or sweeter bianco vermouth (originally invented for the ladies, apparently…) and then get sampling. You might find Billy’s previous blog (complete with vermouth tasting notes) useful in your search.

How to drink vermouth

Since its inception all those years ago, vermouth has been a solid staple of Italian drinking. Funnily enough, although we tend to see it as primarily a cocktail ingredient, in Italy it’s drunk simply – often just with lemon peel and ice in a wine glass or coupette. For a longer drink, try mixing 2 parts vermouth and one part soda, and drinking over ice and lemon as you would a G&T. Red vermouth is also a disturbingly fine pairing for good-quality chocolate, particularly the nutty variety.

For snazzy drinking at home, however, I think you need a bottle of red vermouth and one of Campari on your bar at all times, because these two things combined are the basis for a raft of delicious Italian aperitifs. Mixed together they make the Torino-Milano Cocktail (which sounds a bit like a train line), but in my opinion it’s when you add one more ingredient that the real magic happens:

- add gin = Negroni

- add prosecco = Negroni Sbagliato (this means ‘messed up’ and is allegedly the result of a careless bartender adding prosecco rather than gin by accident.)

- add soda = Americano

If you need any more of an excuse, Tatler have declared the Negroni to be one of the ‘in’ drinks for 2018. I wonder if anyone’s told the Italians?

Enjoy responsibly

Enjoy responsibly

Comments

HI guys, great post – there might be a typo in the level of sugar in each subcategory, particularly the one vis a vis Dry? (currently says 20g, but is it meant to be 50g?)

Hi Claire, well spotted, thanks! Will correct this now.