If you want to host a masterclass on how whisky ages, why not get one of the most knowledgeable people on the planet to run it? That’s what happened at this year’s Whisky Exchange Whisky Show, where Suntory chief blender Shinji Fukuyo went to great lengths to explain this key part of the whisky-making process. As expected, there were plenty of words I didn’t understand (cyclotene, ferulic acid and trans-lactones, anyone?) but Shinji explained the science in practical terms for the mere mortals in the room.

First off, some thoughts on whisky maturation itself:

‘For me, if there is no maturation, then the spirit isn’t whisky; it’s a sort of vodka’ – Dave Broom

‘Up to 70% of the flavour and character of a whisky is formed during the ageing process’ – Michael Jackson

‘Maturation is an essential process that brings out the best characteristic of the whisky and works to refine it even further’ – Suntory Whisky Handbook

What happens during whisky maturation

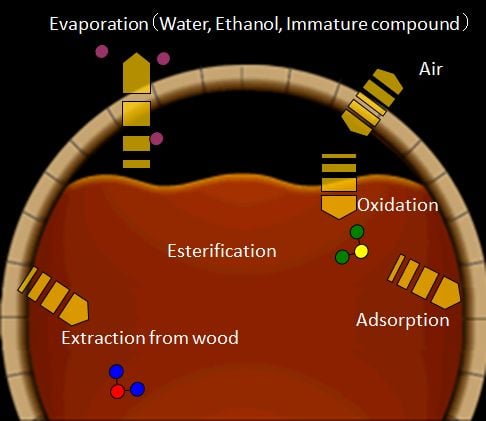

- extraction (from the wood)

- oxidation (the effect of air in the barrel on the whisky)

- adsorption (whisky soaking into the cask)

- evaporation (a mixture of water, ethanol and immature compounds)

- esterification (the formation of flavour compounds)

The key factors that decide maturation quality

- new-make spirit

- cask

- storage method

- environment

New-make spirit

With new-make spirit, Shinji says a number of questions need to be asked, all of which can only be answered with experience: how will the flavours change, when will they be at their peak, will any defects disappear and which brand will be the best match for the particular whisky?

Cask

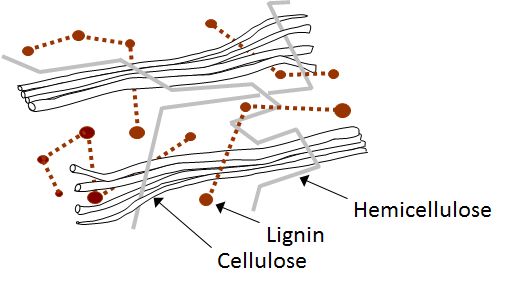

Clearly, casks have a huge effect on whisky maturation given that they are the vessel used to store whisky while it matures. In terms of structure, the cell walls of oak barrels are made up of three main components – Shinji used the analogy of a concrete building to show their respective roles:

- cellulose (‘the steel frame’)

- lignin (‘the concrete’)

- hemicellulose (‘the wire connecting both’)

As the whisky ages, these components will add their own character to the whisky. When the barrel is charred, the cellulose elements will convey notes of fruit and caramel; hemicellulose will offer a more pronounced ‘woodiness’; and lignins will bring the familiar vanilla character often found in whisky.

The cell walls of oak barrels are made up of three main components, all of which convey different flavours to the whisky

A maturing whisky can also be ‘seasoned’ – ageing in a different type of cask than the one it was matured in previously. This does two things, according to Shinji:

- reduces woodiness

- adds flavour from the previous contents of that cask (such as bourbon, sherry or red wine)

To prove his point, we tried two 12-year-old Yamazaki whiskies, both aged in Spanish oak. The first was unseasoned (spending its entire life in one type of cask), while the second was seasoned in a second sherry cask. The result? The unseasoned whisky was rich, dry and spicy, while the seasoned version was a little sweeter with a touch less oak influence.

Storage method

The way that whisky barrels are stored has an effect on maturation, too. There are three main styles: dunnage (where barrels are traditionally stocked no more than three high); racked (stored on shelves with air space around them, often several racks high); and palletised (barrels are stacked on their ends on wooden pallets, usually very high – space-efficient but differing levels of evaporation).

In addition, there are a number of further variables that play their part:

- filling strength – the ideal ABV (alcohol percentage) for extracting compounds from an oak barrel is 60%

- temperature – the higher the temperature of the maturation environment, the more tannin is extracted and the darker the colour of the whisky

- humidity – whisky aged in a very humid climate will see its alcohol level decrease as it is matured; conversely, whisky aged in a low-humidity climate will see its alcohol level increase

Environment

Shinji explained that the location and climate of the maturing whisky changes its flavour and character, too. To use examples from his company’s whiskies:

- Yamazaki (Japan) – smooth, mild character

- Hakushu (Japan) – dry and crisp

- Bowmore (Islay, Scotland) – sea-salt aromas

- a damp cellar – earthy aromas

Japan has four distinct seasons, with hot, humid summers and cold, dry winters, and an average temperature range of 6°C-29°C, which Shinji says ‘stimulates the “breathing” of casks’ and also explains why whisky maturation occurs 1.6 times faster than in Scotland (which has an average temperature range of 4°C-15°C).

Mizunara oak

The masterclass also looked at the famed mizunara oak often used to mature Japanese whisky. We tried young and old examples, with Shinji pointing out that the two key characters mizunara imparts is coconut and incense (the latter only really noticeable after 20 years’ or more maturation) – very different to the typical flavours from American oak (vanilla) and Spanish oak (dried fruits and chocolate).

Sure enough, the mizunara-aged whiskies we tried followed this pattern. A three-year-old sample was teeming with creamy coconut; a 15-year-old version was much spicier and woodier; and a 47-year-old example from 1969 had waves and waves of aromatic incense, and was unlike any whisky I’d ever tried before.

Thanks to Shinji for a fascinating masterclass, and for doing his best to simplify what is an extraordinarily complicated topic.

Enjoy responsibly

Enjoy responsibly

Comments

So where does time IN cask fit in all of this? Does it matter or not? Is a spirit matured using “the best” of new make, casks, method and environment and left for three years the same as one matured for 20? If not, how is age “just a number”? Discuss.

Age is the time that you allow for all of the processes described above to do their thing. Alter the initial conditions, alter the surroundings and then choose the time to allow the characteristics you want to appear in the whisky to, well, appear 🙂

The ‘age is just a number’ comments refer to the oft used adage (the fault of the whisky industry’s advertising back in the days when they had piles of ancient spirit that they wanted to shift to a market that had previously been told that young whisky was best…) that older whisky is better. It’s just had more time to have the processes of maturation work on the spirit. If the initial conditions and maturation environment and conducive to long ageing, you’ll end up with wood soup if you leave your spirit for a long time. If they are set up for long ageing and you pull the whisky early, you’ll get underdeveloped spirit. It’s all about deciding what you want to create and then using the tools at your disposal to create it.

Oh, I gather that you get older profiles from ageing whisky more and younger profiles from ageing whisky less, so one might infer that age does matter. What I was commenting on was that you could have a piece called “how does whisky age” without really dealing with the fact that age itself is a major factor in the result. The industry, and its boosters, want to say that “age is just a number” because they have a lot of young spirit to sell at high prices (what they want to create) and a lot of low age that they don’t want to discuss in the process – and, furthermore, they only want to apply this “logic” (tools at their disposal) to NAS bottles; NOBODY says that “age is just a number” about something that’s 30+ and $2,000 or more, much less warn people away from it on the basis it might be wood soup.

Far from age “just being a number”, it reflects a vital component of a process that is, by definition, time sensitive – hence the term maturation. What matters far less than the age or the result, which are physically determined, is what people call the result (good,bad or indifferent) or that some want to ignore physics to premiumize their young stock while embracing age to premiumize their older stock.

The industry is currently caught in a profit-driven lie on the subject of age (important here, but not over there, depending upon the label), and it’s one that needs to be denounced.

I assumed you were commenting on the article rather than the state of the industry in general…

Age is just a number and I stand by that comment. It’s not unimportant and I don’t see it being said that it’s unimportant in my comments or in the article above. It is, however, just another component in the creation of whisky and a large number does not imply a higher quality. That is what ‘age is a number’ is used to mean.

How that number then goes on to be reflected in price is a totally different topic and one that merits discussion, but not on this post. Feel free to head over to our Facebook group and vent as much as you’d like. I’ll join in 🙂

https://www.facebook.com/groups/TWEandFriends/

I see, so age is just a number – and if the number was three vs. thirty, the primary difference in the result would be found on the label, not in the bottle? It’s here, and in all the expensive age-stated (potential wood-soup) expressions where the nonsense of “age is just a number” – something also plainly being used to flog NAS expressions – breaks down. Age, pretty obviously, isn’t just a number, when every distillery manipulates and tracks it on every cask for the predictable effects that age creates.

It’s not that age is being said it’s “unimportant” in the article above, it’s that its role is being largely ignored in favour of new-make spirit, cask, storage method and environment – that the least important thing in maturation is duration. If the point is that age doesn’t “guarantee” quality well, then, what (if anything) does and is that any basis either way for omitting age information, at whim, in order to enhance sales? That question can’t be answered because it would show that NAS, one of the industry’s chosen directions, is simple, and self-contradictory, nonsense.