[Welcome to the fifth part of TWE’s trip to Japan last year. You can read the earlier instalments in this saga of inter-continental dramming here, here, here and here.]

The town of Karuizawa is an upmarket holiday resort, with the beautiful scenery in the foothills surrounding Mount Asama making it perfect for skiing and golf (not at the same time, obviously). As well as the distillery, the town of Karuizawa is also home to a Meat Museum, which we drove past on the way to the distillery. Sadly, we didn’t have time to find out exactly how amazing that particular attraction must be. There was plenty of snow still on the ground in March, despite the sunny weather, but the atmosphere was far from frosty as we met with two of the leading lights of Japan’s flourishing bar scene.

Hidetsugo Ueno of Bar High Five and Kishi Hisashi of Star Bar are legends of their profession, proper bartending royalty in Japan. They used to work together at the legendary Star Bar in Ginza (owned by Hisashi-san), but Ueno-san has now got his own place, Bar High Five, which is also in Ginza. More on both of these fine establishments in a later post.

The group in the foothills of Mt. Asama

Ueno-san & Hisashi-san joined us for a spot of lunch in a resort restaurant before hopping on the bus with us as we took the short trip from the resort to the distillery. As the main road curved round the boundary of the distillery grounds we were mildly startled to discover that a pile of Macallan casks on the distillery grounds could be seen through the railings at a set of traffic lights round the corner from the entrance.

And then we were there. The bus pulled into a wide concrete driveway. In front of us was a modern, glass-fronted, very closed-looking building. It didn’t look much like a distillery, and that’s because it wasn’t – it transpired that this was the defunct Musee d’Art Mercian.

The museum was created in 1995 by Karuizawa’s eponymous erstwhile owners Mercian by converting an old whisky warehouse – presumably it must have seemed like a good idea at the time, seeing as they couldn’t be bothered to make enough whisky to keep in it.

We walked round the museum building, empty since being closed in November 2011. The distillery’s grounds were certainly very spacious and picturesque – apparently the low sloping sparsely wooded hills were used as a sculpture garden up until the time the museum closed.

Before I go on with my impressions of the site, here’s a few nuts & bolts facts about the distillery itself:

- Karuizawa at the time of closure had a theoretical capacity of just 150,000 litres per annum, which is five times smaller than Glengyle or Arran and ten times less than Bruichladdich.

- The distillery used exclusively Golden Promise barley imported from Simpson’s of Berwick in Scotland, and did so from 1958 because, according to Mercian’s Head of Production, they believed that it gave the spirit a heavier texture and an oily character that couldn’t be achieved at Karuizawa with newer varieties – and which made it a better spirit for long maturation.

- Golden Promise’s relative inefficiency meant that the wash at Karuizawa only reached 7%. Towards the end of its life, Karuizawa changed from its traditional peated to unpeated malt in an attempt to adapt to the Japanese palate of the time.

- The distillery was home to five wooden washbacks and three stainless steel ones. These washbacks date from 1991 – prior to that the mash was fermented in epoxy-lined concrete washbacks.

- There were four very small Japanese-made stills on the site, three of which were 4000 litres, with the other one just 3800 litres. These stills were direct-fired, switching from coal to gas in 1970.

- In his 2008 book ’Japanese Whisky: Facts, Figures and Taste’, Ulf Buxrud said that only the 4000-litre stills were used to make whisky (two wash stills, one spirit still), and that the smaller still was used to do a second distillation on grape brandy that had previously been distilled at Mercian’s Katsunama winery.

As we walked past a very pretty still on display near the entrance, our hosts Marcin and David revealed that our trip that day was to be the last ever at the distillery, which would be closed to visitors forthwith. The remaining workers who maintained the site were to finally lose their jobs for good.

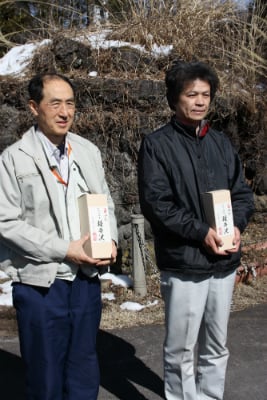

We met two of these workers as we entered the distillery grounds. It was a humbling experience. Here were a couple of unassuming men whose daily routine had once been making the whisky that now sells for such incredible prices around the globe. Since the distillery stopped producing a decade ago they had been tending the buildings and equipment, in the hope that their place of work might one day be called from its mothballed obsolescence, emerging from a tragically early forced retirement to once more make use of their traditional whisky-making skills.

Those hopes had been briefly lifted as various groups of investors had tried to buy the distillery in the intervening period only to be rebuffed by owners Kirin, who had taken over Mercian in 2006; now, with the distilling license returned and news that the entire premises and land had been sold to a mystery buyer, the last hopes were crushed, and these dignified gentlemen were tidying up the distillery site for a final time before being told to leave the premises.

The light that burns twice as bright burns half as long – and Karuizawa, as we now know, burned very, very brightly in its short lifetime. It’s worth remembering that this was not an ancient distillery, but rather modern by comparison to Scotland’s distilleries: although the site was originally a vineyard belonging to a company called Daikoku-Budoshu from 1939, distilling was only begun in earnest at Karuizawa in 1956 after a failed attempt to make whisky at another site owned by the company in Shiojiri, and even then it was only to produce bulk whisky for mass-market blends.

Indeed, Karuizawa’s single malts were few and far between during the distillery’s lifetime, and were unavailable outside their homeland, where they were not highly regarded. The vast majority of the distillery’s output had been used for parent company Mercian’s blended whiskies (Mercian had merged with Daikoku-Budoshu in 1962). The most notable of these was the famous ‘Ocean’ brand, which at one time had some rather racy labels, explored with admirable thoroughness by Nonjatta.

The distillery had its own cooperage making casks from Japanese Mizunara oak (Quercus Mongolica) until 1960, when maturation was switched to imported sherry and bourbon casks at a ratio of approximately 90% to 10% respectively. This was to prove fundamental to the later flowering of Karuizawa’s malts, as we now know.

The onsite cooperage was adapted to assemble, refurbish and repair the imported casks. We visited it on our trip, but the disused tools and workbenches were unsettling. I kept expecting someone to come in and tell us to clear off. Marcin found, and seized upon, a barrel stencil which he waved about delightedly like a trophy. I contented myself with pocketing a trio of abandoned bungs (feel free to insert your own corrupt blogger joke here).

Abandonment was the over-riding feeling at the site. Walking around the Karuizawa distillery inspired a very confused mix of feelings ranging from privilege and gratitude through to pity, guilt and anger that what on the surface seemed like a perfectly well-kept distillery was shortly to be dismantled. Viewing the dried out wooden washbacks and tiny, dusty, brick-encased direct-fired stills was, not to put too fine a point on it, the whisky equivalent of gawping into an open coffin.

This was not a desolate place like the ramshackle ruins of Port Ellen, where the decay is so tangible. Karuizawa, with the eerie reek of vanished whisky in the stillhouse, the smell of dead leaves in its washbacks and a smattering of empty casks bumping against the chains on their racks in the warehouses, was more like a ghost town – a Marie Celeste of a distillery where if you didn’t look too closely you might think that everyone had just popped out to lunch.

We stood in the snow outside one of the grey stone warehouses covered in dead ivy; a bottle of David & Marcin’s young Asama vatting was popped open. A dram was poured on the floor in offering to the spirits, so recently departed from this site. We tried to cheer ourselves up with a few swigs. It was a salutary moment.

As we left the distillery and strolled somewhat dejectedly through the grounds of the closed museum, I noticed a sad-looking little stoneware puppy sitting in the snow near the doorway at one of the rear exits. He seemed symbolic. I was going to liberate him, but thought better of it. So it goes.

Enjoy responsibly

Enjoy responsibly

Comments

[…] some amazing Japanese whisky bars. The previous posts can be found here, here, here, here, here, here and […]