Barrels at Jack Daniel’s

We take casks for granted. In fact, we take all waterproof containers for granted. I think it’s fair to say that in all of human history it’s never been so easy to transport liquids, from the soon-to-be-less-ubiquitous plastic water bottles and coffee cups to IV bags and fuel tankers.

Yet despite all these inventions the cask is still special, and it’s been special ever since people smashed their amphorae with joy at the realisation they’d found something leak-proof that was easier to stack. So when did the cask, to which booze owes so much, come into use, and who invented it?

In the beginning…

…there was pottery. The earliest recorded booze humanity has thus far found was scraped off a piece of pottery that dated to around 7000 BC, and as anyone who’s seen one of those wibbly-wobbly Greco-Roman vases can attest, pottery was a preferred option for thousands of years.

Amphorae under the Roman arena in Pula, Croatia. Image copyright: Caroline Roddis

There were two main types of pottery used. Alcohol was fermented and aged in large earthenware jars called dolia, while the smaller amphorae were used to store it. Their ability to be tightly sealed meant they could keep wine in good condition for years, and they are a key factor in the evolution of the wine cellar in the classical era. These vessels weren’t unique to ye olde swords and sandals times, either: similarly-shaped Georgian kvevri date back to at least 6000 BC, and amphorae crop up in China around 4800 BC too.

Yet pottery wasn’t the only option. Three-thousand-year-old tightly-lidded bronze vessels have been found in China, both in Anyang and the Yellow River Basin, containing wines made from rice and millet that had been flavoured with various herbs and flowers. And of course there was always the biblical favourite, the wineskin, ideal for smaller amounts and personal use – or maybe some kind of soggy hemp version if you were vegan.

Basket, vulture, cloth, basket

Or something…

Historians haven’t yet pinned down who exactly invented the cask, not least due to the unhelpful fact that wood degrades and old stuff repeatedly gets smashed up and / or used for other things over time.

The earliest traces that have thus far been found are from the burial place of Third Dynasty surgeon Hesy-Ra, which features carvings depicting barrel-like storage containers full of grain, dating them back to at least the 2600s BC. Wall paintings from 700 years later, found in the archaeological site of Beni Hassan, also depict similar tubs of raisins, albeit white-coopered ones – those with straight sides rather than the curves we normally associate with casks.

At this point, however, there’s no evidence of liquid involved – unless those raisins are an elaborate Egyptian metaphor for heavily-sherried whisky?

The oars of Babylon

Things get a bit easier to trace when we get past 500 BC, when writers get involved. (Writers, obviously, being the best of all people.) Herodotus, famed Greek historian and unexpected protagonist in the Assassins Creed game I’m currently playing, visited Babylon around 450 BC and described watching wine casks made of date palm wood be ferried down the river on row-boats.

It’s not clear, however, whether or not the Mesopotamians used hoops to secure these barrels, and given that they waterproofed their leather-and-willow row-boat hulls with pitch, it’s possible they did the same to their barrels. If anyone can correct me on this conjecture I’d love to hear from you.

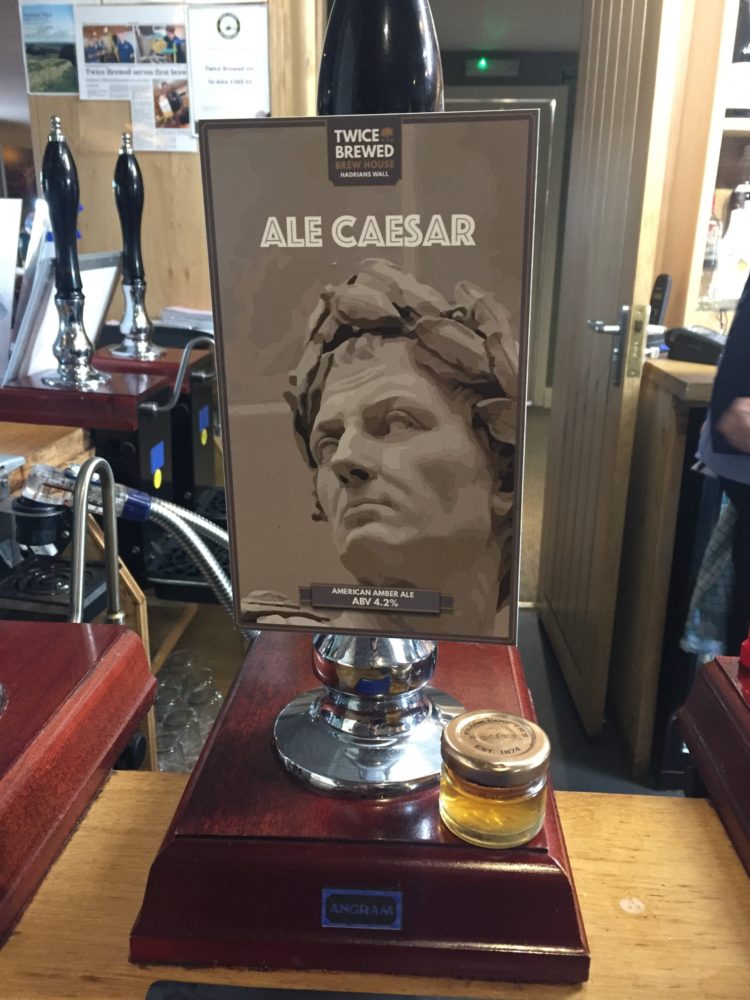

Ale, Caesar!

I stole this joke from the lovely Twice Brewed Inn brewpub in Northumberland

Just after BC turns to AC, we find a number of classical writers passing comment on the Celts and their wooden casks. Strabo, the Greek historian known for writing the Geographica, mentions the ‘wooden Pithoi’ of the Celts being larger than houses, coopered to an excellent standard, and sealed with pitch. Rome’s Pliny the Elder, meanwhile, states that ‘In the vicinity of the Alps, they put their wines in wooden vessels circled with hoops’.

It seems that, over the next hundred or so years, the Greek and Roman world adopted the wooden cask and in particular the hooped oak version they discovered from the Celts, for whom the art coopering was often a family or tribal secret, something that perhaps explains why they took some time to be adopted elsewhere.

It’s not hard to see why the switch from clay to cask was made: casks are less likely to break in transit, can be easily (ish) moved by rolling, and are easier to clean and reuse than pottery vessels. Like clay, wood also allows for the exchange of oxygen, and we can only assume the added influence of oak character on the booze inside was found to be an extra benefit.

Quo cadis?

Today it’s impossible to imagine a wide variety of drinks without the influence and benefits that casks bring to them. It would seem, however, that identifying the original creator of the cask is, at present, impossible – although during my research I’ve encountered some wonderfully inventive theories, including the idea that the first casks were made of bamboo. (Based solely on the idea that they’re hollow, waterproof and therefore most of the way there anyway.)

Yet what we can do, for now, is identify the people who should really be singled out for praise in all this: the coopers, who for millennia have been building and improving on this marvellously simple yet complex invention – one to which we, and our drinks, owe so much.

Enjoy responsibly

Enjoy responsibly

Comments

[…] concept of the wooden cask hasn’t changed much since it first came into being, but the practice of making it has gradually been refined over the past few […]