Ever since the early days of whisky production, distilleries have appeared and disappeared. Some failed, some merged, some literally exploded, and the Scottish landscape is littered with the remains of historical distilling. However, October was a busy month for the lost distilleries of Scotland.

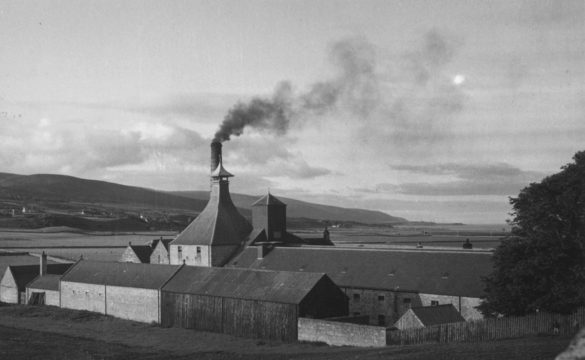

Port Ellen in its heyday. Not much of it’s left these days…for now

It’s not every day that it’s announced that a closed distillery is to reopen, but two on the same day is unheard of. At the beginning of October, Diageo announced that it was going to reopen Brora and Port Ellen, both closed for more than 30 years. Not to be outdone, the very next day, Ian Macleod, owner of Glenoyne and Tamdhu, announced its news: Rosebank distillery, closed since 1993, was also going to reopen.

Why do distilleries close?

While we whisky lovers often take a more romantic view, whisky distilleries are, in the end, businesses. Unfortunately, this means that business decisions are made and distilleries close. Sometimes, as was more often the case in the more distant past, companies went bankrupt or couldn’t afford to keep distilleries open. However, more recently there have been more pragmatic decisions – when the whisky industry isn’t doing so well, companies who own multiple distilleries have closed some of them.

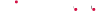

Brora in the 1930s. Most of it is still there

This is what happened in the case of Port Ellen, Brora and Rosebank. In 1983, the year that Port Ellen and Brora closed, and a decade later in the case of Rosebank, many distilleries across Scotland stopped production. The demand for whisky had fallen and the producers needed to save money. The Distillers Company Ltd, owners of all three distilleries, decided that they were surplus to requirements and closed them all – Caol Ila produced similar whisky to Port Ellen, Clynelish produced enough whisky without the assistance of Brora (which was right next door), and Glenkinchie fulfilled the company’s needs for the light Lowland whisky that Rosebank has become well known for.

At the time, single malts weren’t as popular and the closures didn’t cause much of an outcry. However, years later, whisky from all three distilleries is now held in high regard and changes hands for thousands of pounds a bottle.

Why do whiskies from closed distilleries cost so much?

A simple question with many answers. The easiest is just rarity: the closed distilleries aren’t making whisky any more, and as people drink it, there’s less of it available each day. Whether it’s old bottles, filled years ago, or casks of whisky, there won’t be any more once it’s gone.

Rosebank is now mostly offices and apartments, but some of the original buildings still remain

Also, the whiskies that are still in casks are getting older. With that, the price is rising thanks to not only the angels taking their share but also the usual year-by-year costs of nurturing a cask to maturity.

Thankfully, while the owners (and former owners) of closed distilleries often don’t have much stock left, the independents are helping to fill the gaps. Gordon & MacPhail, Signatory, Douglas Laing and Hunter Laing all have great stocks from lost distilleries. Whether you want a bottle of recently closed Imperial, long-lost Dallas Dhu or super-rare Kinclaith, the independents have you covered.

Enjoy responsibly

Enjoy responsibly

Recent Comments

Unfortunately, the answer is 'between 400g and 2000g per litre' :)

Posted on: 9 October 2024

What ratio of Sloe to gin is used, I see anything from 400 to 2000g of sloe to 1 litre of gin!

Posted on: 7 October 2024

What really makes Bob Harris' predicament in 'Lost In Translation' so absurdly funny is that he nailed it in one take, and the director just couldn't accept that.

Posted on: 11 January 2024