[Welcome to the sixth instalment of our trip to Japan. Readers with too much time on their hands can catch up on the full story so far here, here, here, here and here.]

After the emotions stirred up by our trip to the Karuizawa site, it was a subdued and suddenly weary group of travellers that boarded the bus and headed to our next destination, the Hoshinoya ryokan, where we were staying the night before returning to Tokyo. It was a short trip. As the coach twisted up the winding road alongside a bird sanctuary, disconcerting road signs warned of weird-looking wild animals that might assault us on the path and I thought about the history of Karuizawa in the west.

In Europe, Karuizawa first came to serious attention only a few years ago, when Marcin Miller & David Croll’s Number One Drinks Company began acquiring casks to be bottled specifically for the European market and importing them alongside Ichiro Akuto’s Card Series bottlings of Hanyu. Prior to the first Number One imports, the only English language reviews of Karuizawa I have found were in Whisky Magazine, which reviewed the official bottling of 17 year old three times from 2002-2007. These reviews started tepid and deteriorated, with Dave Broom rating the 17 year old as low as 65 points in June 2007, with the comment ‘Just plain odd.’

In Europe, Karuizawa first came to serious attention only a few years ago, when Marcin Miller & David Croll’s Number One Drinks Company began acquiring casks to be bottled specifically for the European market and importing them alongside Ichiro Akuto’s Card Series bottlings of Hanyu. Prior to the first Number One imports, the only English language reviews of Karuizawa I have found were in Whisky Magazine, which reviewed the official bottling of 17 year old three times from 2002-2007. These reviews started tepid and deteriorated, with Dave Broom rating the 17 year old as low as 65 points in June 2007, with the comment ‘Just plain odd.’

Dave had visited Karuizawa in 2005 for Whisky Magazine, and wrote a very interesting piece. He was shown around the distillery by Mercian’s head of production, who waxed lyrical about Karuizawa’s commitment to Golden Promise barley but gave no indication that the distillery had been mothballed some years previously.

TWE first started listing Karuizawas from Number One Drinks towards the end of 2007, at around the same time that Whiskyfun’s Serge Valentin published some very good reviews of Japan-only Karuizawa bottlings on the Japanese whisky blog Nonjatta.

The Number One Drinks releases quickly made a name for themselves when, barely a month after arriving on our shores, a 1981 single cask Karuizawa shocked the European whisky scene by marching off with a Gold Medal from the Malt Maniacs Awards 2007, the first of a slew of awards from what is comfortably the most well-respected independent whisky competition in the west.

Right from the start the prices raised a few eyebrows, although nowadays one looks back ruefully. That 1981 Karuizawa cost £74.99 in the UK, and still took over three months after the Malt Maniacs Awards to sell an allocation of less than 100 bottles. Nowadays a Karuizawa from the same vintage is released at over three times that price, sells out in 24 hours, and frequently can fetch twice or three times its selling price on auction sites within a few weeks.

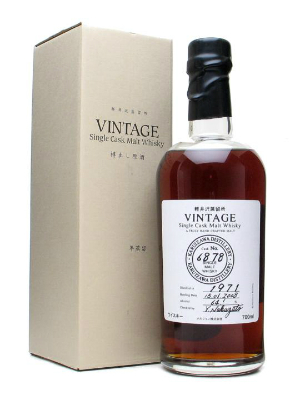

Still the greatest, in my humble opinion

In December 2008, a 1971 Karuizawa 37 year old that had been released and sold out earlier in the year repeated the feat of winning a coveted Gold Medal from the Malt Maniacs – one of only six Golds awarded that year – and also picked up the ‘Thumbs Up’ Award for most exciting new release of the year in the Ultra-Premium category. It was clear by now that the previous year’s Gold Medal for the 1981 was no fluke and that Number One Drinks were onto something rather special.

Just a few months later, in early 2009, a bottle of the 1971 appeared on Europe’s largest whisky auction site. It sold for €303 euros (the initial release price at TWE was £110). To put this into context, in the same auction a bottle of Port Ellen 2nd release sold for €200.

More bottles of the 1971 were listed on the same site over the course of the next twelve months, climbing to a high of €527 Euros towards the end of 2010, just eighteen months after the UK release. The only Port Ellens in the same auction to achieve more were the 4th release (€555) and the 1st release (€1010).

That Port Ellen 4th release still appears regularly and can now fetch up to €1000 euros in auctions on the same website; almost three years on from the last sale, it’s difficult to tell what the Karuizawa 1971 would reach, though it’s not hard to imagine it going for a similar figure, or possibly even more.

And so it continued. In late 2009 the now-legendary Karuizawa 1967 cask was bottled by TWE and our French friends La Maison du Whisky, but was not entered for the Malt Maniacs Awards as the stock had not arrived in time. Instead, a 1972 cask bottled by Number One Drinks took the distillery’s now-traditional Gold Medal for that year.

The 1967 sold like wildfire nonetheless, thanks to an unprecedented (for Japanese whisky) score of 95 points from the doyen of whisky tasters, Serge Valentin of Whiskyfun, whose notes were published online a few weeks before the TWE version hit the shelves. This humongous 58.4% sherry monster was until recently the oldest Karuizawa ever bottled and again the value shot up in the secondary market, reaching €925 euros within a year on a whisky auction site.

Further scores of 95 points from Ruben Luyten (Whiskynotes) and 96 points from Jim Murray in the Whisky Bible increased the status of this bottling still further, and at the time of writing the asking price of the only bottle I could find for sale is €2500 at an online whisky retailer, representing almost ten times the original retail price only three and a half years after being released.

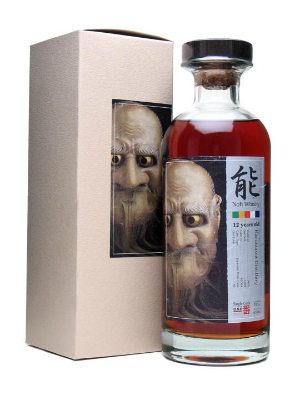

In 2008, Number One Drinks introduced the Noh series of Karuizawa bottlings, originally using casks that didn’t fit the classical Karuizawa profile of their official ‘Vintage’ series. Noh is an ancient form of Japanese theatre with strong religious connections – Nonjatta has explained Noh performances as akin to a religious ceremony – and the lead character in a Noh drama wears a mask that the performers somehow manage to convey different emotions with by changing the mask’s position in the light. Once again, I’m indebted to Nonjatta for this amazing link that clarifies what I’m trying to explain, as well as for most of the information in the following couple of paragraphs.

The very first Noh bottlings were actually of Scotch whiskies and were 200ml bottles sold at performances of the Kamiasobi troupe of Noh performers in collaboration with Number One Drinks. Soon Karuizawa was added to the list of these bottles, and subsequently Number One expanded the Noh range to include full size bottlings for foreign markets.

The Noh bottlings were released in decanter-style bottles featuring a striking image of one of the Noh masks used in performances, with a royalty from each bottling going to the Kamiasobi troupe in return. These bottlings were an instant smash hit, with enthusiastic drinkers and collectors scrambling to acquire the Noh series’ sometimes beautiful and occasionally quite scary labels. To this day, the release of any new bottle in the Noh series remains a major event in the whisky world.

These days, as the fame of Karuizawa has spread, the demand for Karuizawa from the 1980s or earlier is huge, and as almost all new releases tend to be single casks, the supply is limited to only a few hundred bottles.

The prices have risen accordingly – nowadays it’s almost impossible to believe that TWE took three months to sell out our allocation of the 1971 vintage (which was only a fraction of the 400-odd bottles yielded from the cask) at £110 per bottle. Or that our 10th anniversary 1982 single cask (£120), released in November 2009 at the same time as the 1967 (and which I confess I preferred to the ’67, although the ’71 is still at the top of my all-time list) was still available until September 2010, although it had gone up to a whopping £125 by then, thanks to the intervening budget and VAT rise.

The very high prices that Karuizawas now go for reflect the fact that many more people want to buy these whiskies than stock exists to satisfy, and of course there are some speculators in there looking to make a quick buck. However, there may not be quite as many Karuizawas stashed away in dusty collections or changing hands between investors and collectors as we think – in fact, there are many Karuizawa fans in Europe (and even more in the Far East) who want multiple bottles of Karuizawa to drink.

This last issue raises another point. Bearing in mind that so many Karuizawas are bottled for the European market and the early Mercian-era Karuizawas were not especially popular in Japan, you might assume that it’s only Europeans that are buying Karuizawa. This is absolutely not the case. A very significant proportion of each Karuizawa release that comes to market in Europe is being bought online by the fistful by voracious Karuizawa drinkers in the Far East including Singapore, Taiwan and, yes, Japan.

It is certainly not surprising that Japanese drinkers failed to be enthused by the mostly mediocre Karuizawas that Mercian released during the distillery’s lifetime. But, just as with a distillery such as Benriach, we can now see that great whisky was always there – it just wasn’t being selected or managed in the correct way, and the reputation of the distillery suffered as a result.

It’s now clear that Karuizawa was fatally mishandled under the previous owners who let it die through wilful negligence and actively thwarted all attempts to revive it. They must carry the shame of this mindless destruction of a beautiful, important distillery. But there’s no doubt that the malt produced at Karuizawa is resonating now with many modern whisky drinkers of all nationalities. Karuizawa is gone, but it will never be forgotten while this generation of whisky drinkers are still above ground.

Back in the Japanese highlands, we arrived at our accommodation for the night, the sumptuous Hoshinoya ryokan. I’ve talked about ryokan before as we’d stayed in one the previous evening, but the ultra-modern Hoshinoya couldn’t have been more different than the ultra-traditional Aramoku Kosen, although the philosophy seemed to be the same – total guest comfort and relaxation.

Like Aramoku Kosen, Hoshinoya had its own hot springs (onsen), but where the rooms at Aramoku Kosen were all dark wood, sliding doors and tatami mats, the facilities at the complex of chalets at Hoshinoya were more akin to a luxury hotel with enormous mattresses lined up against the wall, a large lounging area and natural stone shower room. There was even a sofa on the wooden-floored area overlooking the Yukawa river that flows through the resort. Guests were being ferried around in tiny little white cars that looked like sugarlumps on wheels.

In our room we found an information leaflet telling us about the resort. I was secretly relieved to discover that I would be forced to forego the hot springs once again, this time as the resort politely requested those with tattoos to refrain from using the onsen ‘as a courtesy to Japanese customs’ (translation: No Yakuza, Please, We’re Posh.)

The reception-cum-restaurant at the resort was cavernous as well, all exposed stonework and fancy light fittings. We dined there in the evening – a superb, many-coursed meal of modern Japanese cuisine – before heading back into Karuizawa to visit the local branch one of Japan’s most legendary bars: Helmsdale.

Helmsdale is, and I mean this in the best way possible, an utterly bonkers bar run by an utterly bonkers man. You may have an idealised notion of what a whisky bar is, some Platonic ideal of leather seats and oak panelling. Helmsdale is not that. Helmsdale is, essentially, a wooden shack, a glorified garden shed stuck by the side of a major road. However, it’s almost certainly the best glorified garden shed in the world.

Masaki Murasawa, the owner of Helmsdale, loves Scotland. Actually, that’s not quite right. Murasawa-san LOVES Scotland, and the UK generally. His business card even has an ‘I heart Scotland’ logo in the top left corner. Not that you’d forget meeting him. The man positively radiates charisma and enthusiasm. Murasawa-san very kindly opened his bar for us, and the ten of us filled it.

There were two tables in the bar. The back wall was covered three deep in bottles of whisky teetering on ancient shelves. Every other interior surface was festooned with British food and alcohol-related nick-nacks, memorabilia, toast racks, Beatles albums, ashtrays, butter dishes, bar towels, teapots, Scottish flags, bar signs, salt cellars and egg cups, many of them animal-shaped and/or decorated with union jacks or saltires. I can’t possibly do it justice.

There was a television up in one corner on which one can watch Premiership, La Liga or Champion’s League football. Helmsdale’s sister bar in Tokyo (which by all accounts is not much bigger) even has its own football team, Helmsdale FC. Everything else could have been transported in a time machine from the 1960s-70s.

It was a cold night, but we warmed up quick. Murasawa-san imports kegs of Scottish beers for Helmsdale, of course, although he had some bottles of English ale, Guinness and even Aspall’s cider sitting on the bar as well. He also brews his own beer and the bar does western food. His hot dogs and fish & chips are both legendary in the area and bottles of Sarson’s vinegar and Heinz ketchup sit proudly on the bar. The kitchen is a small green Japanese campervan, parked outside.

We clustered round our pints of heavy and began gawping at the back wall’s mouthwatering array of whisky. Egad, is that a Macallan 1965? Clynelish Prestonfield? Mortlach Book of Kells ’38? Bunnahabhain Samaroli? Douglas Laing Ardbeg?!

I considered making notes, but quickly decided not to. For one thing, there wasn’t any room to do so. For another, sod it – Helmsdale is far too much fun to be messing about with scribbling. If you’re ever in Japan you have to go. If you can’t make it to Karuizawa the original is in Tokyo – incredibly, this little slice of nirvana is merely an offshoot. There’s really no excuse not to drop in.

After the sadness of the Karuizawa site visit this was the perfect pick-me-up. It was impossible to be in Murasawa-san’s presence without being infected with his joie de vivre and fervent love for whisky, and it was not without regret that we eventually succumbed to our long, emotional day and retired to the ryokan.

Enjoy responsibly

Enjoy responsibly

Comments

[…] amazing Japanese whisky bars. The previous posts can be found here, here, here, here, here, here and […]

[…] visited. Time-rich insomniacs can find the previous instalments here, here, here, here, here, here, here […]