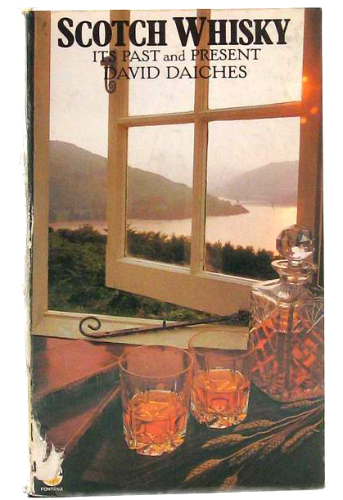

David Daiches’s book Scotch Whisky: Its Past and Present, first appeared in 1969, and was popular enough that a revised edition appeared in 1976, of which my copy is the paperback. I am not sure where I picked it up – it has no second hand price pencilled on the first page, but it seems unlikely that I pilfered it from my parents, who are the source for a large quantity of the 1970s paperbacks on my shelves (at least the ones that aren’t pulp detective fiction). It may have belonged to one of my grandparents. [N.B. If you’re seeking this book out, the hardback version is a larger format and has more photos and illustrations.]

In any event, I had thought this marvellous book lost, but found it recently when I moved house and immediately ploughed through it again at speed. Like most, if not all, of the whisky books before Michael Jackson’s ground-breaking Malt Whisky Companion, Daiches’s book focuses more on the industry and the production of Scotch than on the taste of the liquid; where he talks about specific brands, it is more about their history and position in the industry; tasting notes are cursory and impressionistic.

In the 1960s and earlier, of course, there was no such thing as a professional whisky writer. Regrettably, it must be said that many of the whisky texts I’ve encountered from this era were rather the better for it. I’m not being grumpy or nostalgic when I say this – it’s just a fact that whisky books back in the day were generally written by writers or gentlemen scholars with an interest in whisky rather than drinkers with writing aspirations, and it really does make a difference.

These early enthusiasts did not rely on their whisky writing to put food on the table and keep a roof over their family’s heads. Daiches’s writing seems wonderfully relaxed. His sentences are well-constructed, his arguments well-structured and his anecdotes and asides give the pleasing impression of an easygoing conversational monologue, although he never diverges too far from his point and his opinions are always backed up with facts and stats where relevant.

Daiches’s writing prowess is in no doubt largely due to the fact that in his day job this enthusiastic whisky fan was an extremely distinguished literary critic and cultural historian. Daiches was born in 1912, the younger son of a Lithuanian rabbi, and had moved to Edinburgh from Sunderland around 1920.

In 1969, when the book first appeared, Daiches was 56 years old, Professor of English at Sussex University and 35 years into a stellar academic career which had included spells of teaching at both Oxford and Cambridge (he was a Fellow of Balliol College, Oxford at the age of 23 and later spent a decade teaching at Jesus College, Cambridge) as well as extensive visiting professorships in the United States; his American experiences are the source of several enlightening and entertaining anecdotes in the book.

Daiches was an astonishingly prolific writer. Scotch Whisky was his 29th published book, and his other notable works included standard texts on authors and subjects including Virginia Woolf, Milton, the Scottish Enlightenment, Robert Louis Stevenson, the King James Bible, Bonnie Prince Charlie, Sir Walter Scott, Robert Burns and, subsequent to the publication of Scotch Whisky, two books exploring the social and cultural histories of Glasgow and Edinburgh. Anyone in the UK who took Eng. Lit. beyond O-level or GCSE will likely be familiar with the enormous Norton Anthology of English Literature, of which Daiches was one of the original editors.

By the time of his death in 2005, at the age of 92, Daiches had published over 50 books and innumerable articles and monographs. He was one of the 20th century’s foremost authorities on Scottish literature. If you’re interested, here’s a great interview with Daiches that appeared on Scottish TV in 1989.

Scotch Whisky, however, is anything but a dry academic text. On the contrary, Daiches uses his skills as a cultural historian to weave facts about the whisky industry and Scottish history with his own passionately-held opinions and seasons his text with the occasional understatedly amusing anecdote. His scholarly leanings reveal themselves in the frequent use of brief quotations, particularly from historic texts: the bibliography at the end of the book is very interesting and I’ve already invested in more than one of the several books on the list that were previously unknown to me.

Daiches’s writing is a pleasure. In the first part of the book he tells the story of the development of distilling, then gives a detailed but easy to follow description of the processes of making single malt. The book is a joy right from the start – after a page of extolling the beauty of Scotland, Daiches brings his readers abruptly down to earth:

” Scotland…is neither a stage backcloth nor a film script…its best known product, Scotch whisky, is not a whimsical mountain dew distilled by pixies, but a spirit produced by human art…”.

A few paragraphs later, Daiches starts flexing his literary chops with this priceless zinger:

“Douglas Young, the Scottish poet and scholar, used to maintain that whisky was invented by the Irish as an embrocation for sick mules and that once it was brought to Scotland its use was perverted from external animal application to internal human consumption. But Young was not a whisky drinker and his account is clearly an amusing invention.”

Of course, Scotch Whisky was written at a time when the distilleries were going through an enormous change, with modernisation programmes about to go into full swing at many distilleries. This was because of the prevailing belief that the Scotch whisky industry was on the verge of a huge boom necessitating large increases in capacity to meet future demand. These modernising forces hadn’t quite taken full control yet, though, and the result is some charmingly outdated technical data.

“There is no universally accepted way of heating the pot stills…coal furnaces with automatic stokers seem to be as far towards modernization as many Highland malt distilleries are willing to go.”

Daiches’s prose also gives the lie to the concept of consistency in single malts, though of course this is hardly surprising in an era when most were not released for commercial sale.

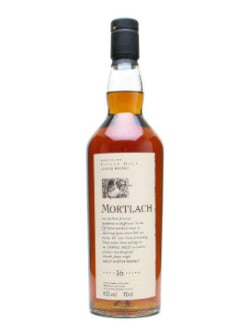

“[In 1950]…I introduced American friends to Mortlach… and they took to it with enthusiasm. Perhaps the fact that it was matured in plain oak and was virtually colourless was held to be in its favour.”

The real joy of Daiches’s book, though, is when the author asserts his opinion, frequently in the bluntest of terms. Daiches begins to let rip properly in Chapter 6, entitled ‘Whisky as a World Drink’, with a long tirade about the diminishing proportion of malt in commercial blends. There are some eye-opening statements.

“[I believe that in]… the standard blend of Scotch whisky today the proportion is 60 grain to 40 malt, and that the proportion of grain has risen since the earlier days of blending, when it was more likely to be 50:50.”

Daiches then moves on to a rather searing denunciation of the use of caramel colouring. It is somewhat depressing to find that the argument (and the industry’s position) is exactly the same today as it was 45 years ago.

“The blenders will tell you that this is to maintain evenness of colour…[and that]…the use of artificial colouring…reassures the public and maintains confidence. I think this is nonsense, and contributes to the rubbish about whisky colour that is perpetuated in whisky advertising…I have seen a skilled tintometer operator carefully working out the amount of caramel colouring…. [for 8, 12 and 20 year old blends]…colouring the whisky according to its age to fool the consumer into believing that the darker it is the older.”

There is more – much more – to enjoy in this book, but this post is long enough already and I don’t want to spoil too much of it for you. Seek it out, you won’t be disappointed. Scotch Whisky: Its Past and Present, though dated in places, is mainly a brilliant historical survey and therefore still very much worth reading for anyone interested in whisky’s social and cultural history and the rise of the industry in the 19th and 20th centuries.

I’ll leave you with this eloquent scholar’s wonderfully lyrical summary of Scotch:

“The proper drinking of Scotch whisky is more than indulgence: it is a toast to civilisation, a tribute to the continuity of culture, a manifesto of man’s determination to use the resources of nature to refresh mind and body and enjoy to the full the senses with which he has been endowed.”

Enjoy responsibly

Enjoy responsibly

Recent Comments

Unfortunately, the answer is 'between 400g and 2000g per litre' :)

Posted on: 9 October 2024

What ratio of Sloe to gin is used, I see anything from 400 to 2000g of sloe to 1 litre of gin!

Posted on: 7 October 2024

What really makes Bob Harris' predicament in 'Lost In Translation' so absurdly funny is that he nailed it in one take, and the director just couldn't accept that.

Posted on: 11 January 2024