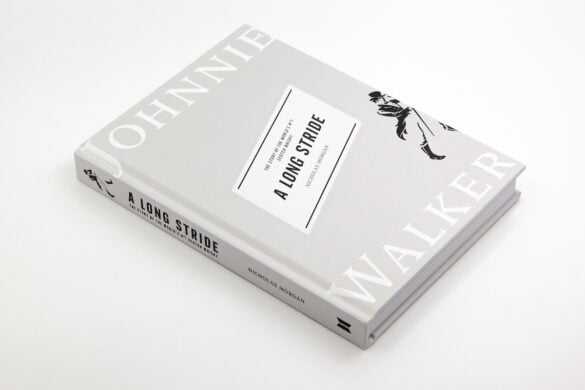

For those in the drinks industry and numerous whisky fans around the world, Dr Nicholas Morgan is a well known figure. With a thirty-year career working for Diageo – starting there even before they company took that name – he’s been most recently known as the public spokesman for the world’s largest whisky maker. However, the past few years have seen him take a break from his role as ‘Diageo’s Human Shield’, to quote the Whisky Sponge, to focus on a different project: writing the history of Johnnie Walker ready for its 200th birthday – A Long Stride: The History of the World’s No.1 Scotch Whisky.

We sat down with Nick before the book hit the shelves to find out more about how a history lecturer became one of the best-known voices in whisky, and what lessons the rise of Johnnie Walker has for both the whisky industry and whisky drinkers.

The origin of Dr Nicholas Morgan

Billy Abbott: Your background is in history and academia – how did you get involved with Scotch whisky in the first place?

Nick Morgan: I was teaching Scottish history at Glasgow university and had been away on a sabbatical doing a piece of work on Glasgow urban history, and I came back and – most people may not understand this now as it was 1989 – I had a massive pile of correspondence on my desk. I spent about two days sifting through all this stuff, and in the middle of it was a letter from a company called United Distillers asking me if I’d like to come down to London to talk to them about taking the position of archivist with the company, which I found quite intriguing. So, I went down and spoke to them and was offered the job of setting up a historical archive for United Distillers.

I was taken on to do that job and I wasn’t an archivist, so I was lucky enough to be able to appoint proper archivists to come and work for me, and spent about three-odd years putting that together. But in addition to doing the archive work, I was pulled into doing marketing work right from the start, and after three or four years discovered that I wasn’t an archivist any more and had some sort of marketing role in a department in London. The rest is history.

A Long Stride: a long-awaited project

BA: How did the book come about?

NM: I’ve had the idea of writing a book almost since joining the business thirty years ago, and certainly in my rather meagre annual performance reviews, when I had to state my ambitions, I can honestly say that for about the past twenty years I’ve simply put every year ‘Write the history of Johnnie Walker for 2020’. So, I made it very clear to people that’s what I wanted to do.

I was also able to talk to some really bright people and explain to them why it would be a good idea to have a history of Johnnie Walker, and people like David Gates, who was running Scotch whisky for Diageo at the time, was a very keen sponsor of this. So the only sort of disagreement was when I would start doing it, and I would have loved to have started a bit earlier than I did, because I could have done a bit more work.

I started about three-and-a-half years ago, spending about 85% of my time researching and then writing the book.

Researching the book

BA: Where did you find the information?

NM: Obviously, the starting point was the Diageo archive, which is a phenomenal resource and brilliantly managed by a team of professional archivists – it’s best in class. In that archive, the Johnnie Walker collection is by far the largest, albeit far from complete, but it’s absolutely huge. In that collection we have a few fragmentary very early records which were very important for piecing together the early history of the business.

From 1857, when Alexander Walker – who was John Walker’s son – took over the business, we have his annual account book, and that’s every year’s stock taking. At the beginning that’s quite detailed stock takes, but as the business gets bigger and bigger and bigger, you can’t fit it all in the book. So, that’s invaluable for seeing how a grocery business that blends whisky grows into an international whisky business in twenty or so years, which is quite phenomenal.

We have correspondence from Alexander Walker in that collection as well, and a whole range of other stuff once it becomes a limited company and there was more legal obligation to keep records. Lots of blending material from the twentieth century, and quite a lot of export-related material as well.

So, there’s a huge amount in there. But in writing the book, we also wanted to put it in a broader context. There was a very clear agreement when I started writing that this wasn’t going to just be a conventional company history, when you start off with the founder and end up with a picture of the chairman in his office and all that – we were doing a proper book to place Johnnie Walker in the context of Scotch whisky and Scotch whisky in the context of whatever else was going on. Very often whisky history is seen through a tunnel vision, and I wanted to expand on that.

To do that from the booze business perspective, I spent a lot of time looking at trade journals, not all of which have been used in the past. Some have – Harper’s, for example – but I found a few that had not been used and were highly informative. Not so much about Johnnie Walker, but more about the Scotch business and the context of that. Also, I looked at newspapers, which has been transformed with all the digital libraries, which Laura Chilton spent a lot of time working on for me. Again, she didn’t find out much about Johnnie Walker, because they hid themselves so very well, but it was really valuable.

Then also a whole range of stuff to put Scotch in the context of popular culture – a whole range of weird and wonderful journals, some of which you’ll see in the footnotes, and others that aren’t there but really informed what we could say about it. Finally, advertising journals, which really unlocked the story of the development of the Johnnie Walker brand through the twentieth century.

Lessons of the past

BA: One of the things that struck me about the history of whisky through the Walker lens are the parallels with the present day. Some of the comments in the book on the early days of whisky are things that you have discussed before about more modern situations. Are there any particular lessons from the history of Johnnie Walker that we need to pay attention to in modern Scotch whisky?

NM: There’s one that people seem to be particularly preoccupied with at the moment. About four or five months ago people started phoning me up from different bits of Diageo saying, “Is there going to be anything in the book about how the brand came through hard times?”

There is a theme of resilience, which is important for today, because I think it would be easy to look at the circumstances we are in and think that the sky’s falling in, but the sky’s fallen in on Scotch many times before, and on the Johnnie Walker brand. While not all brands survive – for example, after the First World War lots of brands disappeared – every time Johnnie Walker’s gone through one of those situations, it’s come back stronger, bigger and better, bouncing back. I think that’s an important message for everyone to have.

I think maybe there’s also a parallel today with the way that people think about the relationship between malts and blends. I was very struck by that coming out of the discussion of the ‘What is Whisky?’ case, and you’ll see there’s quite a lot in the book about it. Also, there are similarities with elitism in the world of whisky, and the idea some whiskies were far superior to others, and particularly that malt whisky was better than blends.

Culturally, that argument becomes quite complicated in the early twentieth century, not least because of the Aeneas MacDonald book [Whisky by Aeneas MacDonald, a pen name for journalist George Malcolm Thomson], which people today consider to be a sort-of bible about whisky. Not only was the book plagiarised, broadly speaking, from a whole range of other people, but it was a polemic, and a polemic written by a not very nice person – Scotland’s best-hated man, as he was known.

The views that he pronounced and his dismissal of people that drank blended whisky – a view that is very elitist and that I find quite offensive – do echo some of the comments that you still hear today from people, and the way they dismiss blends and praise themselves, of course, and single malts. I wanted to make people aware that there is a theme that is there and hasn’t gone away. I’ve also tried to suggest that it’s not really a very pleasant way to think about the category, broadly speaking.

What is Whisky?

BA: I’ve read about the ‘What is Whisky?’ case many times before, but always from the perspective of the malt producers. It’s very interesting to see it from the other side for once.

NM: That was quite an important bit for me. When I went into it, I had certain preconceptions, as you might imagine, writing from the perspective of the blended Scotch business. But I hadn’t really understood the full complexity of the situation and the degree to which these new proprietary brands of Scotch whisky were absolute disruptors in a whole range of very well-established relationships, and they blew all of that apart. The culmination, and if people read the book they’ll see this, is that by the time of ‘What is Whisky?’ everyone was asking ‘Why are these guys still trying?’. The boat has left and they were not on it. But that was the culmination of twenty or thirty years or more of these deeply vested stakeholders struggling to claw back this sort-of preeminence in the business, in the retail trade, in agriculture. I think it has to be seen like that.

BA: The history of whisky seems to have quite a circular nature, with malts back in the early days as the entrenched part of the business and blends as the disruptors. Now blends are the entrenched part of the business…

NM: …and malts are the disruptors! They’re getting their own back.

BA: The final comment in my notes on that section was ‘the power of the consumer palate’: the focus in whisky-making to create something that people like and want.

NM: What surprised me in the research – and this is the stuff that comes through from the trade journals – is that many people emotionally clung to the idea that single malts were better, and that Highland whisky was better than grain whisky, and all of that stuff. But at the end of the day, they all just had to say, “But this is what people want to drink – this is what consumer tastes are”.

Even with blended whisky, you have to remember that styles of blends changed enormously. From the mid-to-later 19th century, you have what I would call ‘toddy whisky’, because for respectable drinkers that was how you would drink it, with hot water and sugar and lemon – if you were lucky: you could never get lemons in Glasgow, people would complain, but that was how it should have been drunk. These were really heavy whiskies – there’s a great description of them in the book – oily and heavy and peaty. Of course, as soon as you start drinking whisky with soda, which became the craze from the late 1890s, then you want a lighter drink.

Styles are always going to change, to reflect what consumers want. I think that’s the same as Walker today: is it the same as it was a hundred years ago? Well, no of course it isn’t, for so many different reasons, but the principle one is what people like to drink.

Insights for drinkers

BA: Are there any insights into whisky from the story of Johnnie Walker for whisky drinkers?

NM: One of the things I think people should be aware of, which I think they’re sometimes a bit dismissive of, is the – I don’t apologise for using this word – obsession that whisky makers have with the quality of their whisky, and it sings through in the Johnnie Walker story. It’s not marketing bullshit, it’s all there, it’s absolutely real. Walker’s, more than anyone, thought that it was quality that sold their whisky, almost to their cost at different points, as they refused to advertise until they were dragged into that in the Edwardian era.

I think…no, I know, from my thirty years experience in the business, that the people who make whisky today, whether they’re distillers or blenders – and they might be quite different people from the ones that were doing it even when I joined the business, and certainly from thirty or forty years before that – they’re equally passionate about what they do, and put their all into delivering the best quality product they can, whether it’s a blended Scotch or a single malt or a single grain. I know, for what it’s worth, that sometimes they’re very hurt personally when they read some of the thoughtless comments that people put on social media in particular now about different brands and different products and different companies.

I think that passion for quality still is at the heart of all of Scotch, and if we lose that, what have we got? We’ve got nothing. And certainly for a brand to be as big as Johnnie Walker and to have persisted for this long, quality, and the consistency that goes with it for a global brand, is absolutely critical.

A Long Stride: The History of the World’s No.1 Scotch Whisky hits the bookshelves on 29 October.

Enjoy responsibly

Enjoy responsibly

Comments

Look forward to reading this history lesson on johnnie walker.