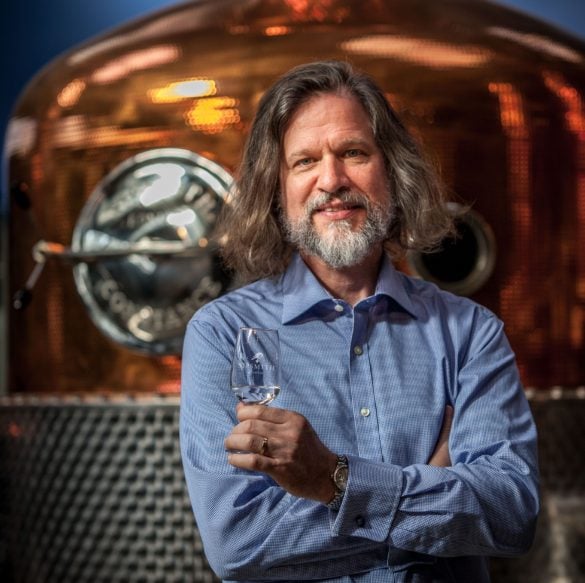

Jared Brown, master distiller at Sipsmith Gin Distillery in London, explains why you should all be drinking sloe gin – and offers some tips on how to make it yourself.

Sloe gin is to Britain what limoncello is to Italy. Everyone makes it at home, and everyone takes pride in their family recipes. Visit a British household over the holidays and the meal will likely finish with glasses of sloe gin. But surprisingly, this cherished sip does not have a long history in the UK.

The Enclosures during the mid-Victorian period was a time when new taxes forced wealthy landowners into bankruptcy. Hedgerows were planted across the countryside to divide fields and pastures among the workers. Two of the most common hedge plantings were blackthorns and hawthorns, as they grow dense and thorny enough to prevent sheep from pushing through them.

Within a few years, British farmers were faced with an abundance of sloe berries, which are blueberry-sized, intensely bitter, wild plums. Resourceful and inventive, they tried making sloe wine. No matter how you make it, sloe wine is awful stuff (even when compared to another countryside classic, parsnip wine, which is actually rather good).

how to make sloe gin

After a few decades of bad wine, some enterprising farmer discovered sloe gin. It was first mentioned in print around 1867, then recipes began to emerge during the early 1880s. These formulae were all very similar to one another and remarkably similar to modern recipes:

Harvest after the first frost. Prick the sloes with a thorn from the tree on which they grew, or prick them with a silver pin. Combine gin, sloes, and sugar in a tightly sealed bottle. Shake once a week for about three months. Use cheap gin; it’s just an ingredient.

Trouble is, this is an awful recipe. Sloes do not desiccate and concentrate their sugars after a frost, like grapes in ice-wine-making. It is just that even when ripe, sloes are intensely bitter, so tasting them is not an option. Pricking them with a pin will rupture the skin, helping them to bleed flavour and colour into the gin, but it is highly inefficient and rather ineffective. A thorn is even worse, lasting for about four sloes before you need another one.

So, how do you harvest when sloes are ripe? Everyone knows what a ripe plum feels like; it is the same with sloes. They also build up a powdery coating of yeast when ripe. And the trouble with relying on the first frost is that it could come in early September when they are unripe or late October when they are raisins. After harvest, freeze the fruit for a few days to rupture the cell structure like a thousand pins.

should i add sugar?

The next step in the recipe: adding sugar to the gin and sloes is a heresy. Sloes do not ferment in the bottle and do not need the sugar unless the goal is not to make sloe gin but to make sloes that are marginally edible afterwards. Sugar saturates the gin, creating an osmotic pressure barrier that does not allow the gin to extract the natural fruit sugars. To make the best sloe gin, add no sugar at the start. Instead, after three months add simple syrup to taste. It won’t require nearly as much as the recipes call for, plus you can precisely control the sweetness.

when is it ready?

How do you know when it is time to remove the fruit and sweeten the liqueur? Sweeten a little of it and taste. Look for what I call the ‘four foundation flavours’ of sloe gin: dark cherry, citrus, cinnamon, and marzipan. Once you find those, remove the fruit. Sloes need to be in the gin for a minimum of a few months, up to a maximum of about six months. After that another flavour tends to emerge, a bit like the taste of an old sponge found under the sink and added to this beautiful liquid.

Some people add crushed almonds – a nice touch that highlights the marzipan taste. Others add a tiny bit of dried orange peel. You can also make it with Irish whiskey instead of gin. This is a fascinating experiment. Gin highlights the bright citrus flavours of the fruit; Irish whiskey highlights rich plum notes instead. Malt whiskies, on the other hand, become a bit musty, while American whiskeys are a little sweet and fiery.

Enjoy responsibly

Enjoy responsibly